This article is part of Brainscape's Science of Studying series.

Chemistry was always a mixed bag for me. On some topics, like organic chemistry, I was the Oracle. On others, like quantum theory, a troglodyte.

As it turns out, every student of every discipline understands what it feels like to be strong in some areas and weak in others. The problem is that most study methods treat every concept as equally difficult when, clearly, our brains do not.

This, my friends, is exactly what confidence-based repetition (CBR) was built to solve: a study strategy that leverages the proven cognitive science principles of retrieval practice and spaced repetition, personalizing it to the individual learner so that they focus their study time attacking their weaknesses.

In this article, we’re going to explore what confidence-based repetition is, how (and why) it works, and the adaptive strategies—notably flashcard apps like brainscape—you can use to incorporate into your study routine right away.

Let’s go!

What Is Confidence-Based Repetition?

Your brain holds onto some ideas with a kung-fu death grip, while letting others slip into the abyss of your memory. (This has a lot to do with your unique interests and experiences in life, so we won’t dive into the “why”. Suffice it to say that this is just how our brains are wired.)

Confidence-based repetition is a study approach that evens the playing field by focusing your time and attention on the concepts you’re least confident in, but without letting you forget your stronger concepts either. It does this by repeatedly exposing you to concepts at intervals of time that are carefully tailored according to how well you know each one.

What does this look like in practice?

Well, if you know a topic well and feel really confident in it, then you won’t need to review it again for a while in order to remember it. But if, on the other hand, you’re not confident, then you should review it again soon, and at more frequent intervals. That’s why it’s called confidence-based repetition: repetition based on your confidence level!

Get it?

Why Is Confidence-Based Repetition So Powerful for Learning?

Confidence-based repetition works because it mirrors the way your memory naturally strengthens: through effortful retrieval, honest self-monitoring, and well-timed reactivation of fragile knowledge. At its core, CBR teaches your brain to become a more accurate narrator of what it actually knows—and what it only thinks it knows—while scheduling your practice at the moments when it will have the biggest impact on long-term retention.

Let’s break all of that down piece-by-piece…

1. Your brain mistakes familiarity for understanding

One of the biggest barriers to accurate learning is the brain’s tendency to confuse recognition (“this looks familiar”) with mastery (“I can recall this from scratch”) (Nelson & Narens, 1990). This is why rereading your study notes or rewatching video lectures often feels productive even though it produces very little learning.

A lot of study habits keep the answer in front of you, which can feel like learning even when it’s not. The infographic below shows the passive vs. active split with concrete examples, so you can tell at a glance which side your studying is landing on.

If you're stuck in the trap of passive learning, CBR disrupts this illusion. Each time you rate your confidence after a retrieval attempt, you are separating the warm glow of familiarity from the colder, more honest signal of “could I actually recall this unprompted?” Over time, this repeated contrast trains your brain to become better at distinguishing true knowledge from the stuff that merely feels known.

There’s a name for this and it’s called resolution (Prime & Burns, 2020). Good resolution = good judgement of what you know and don’t know.

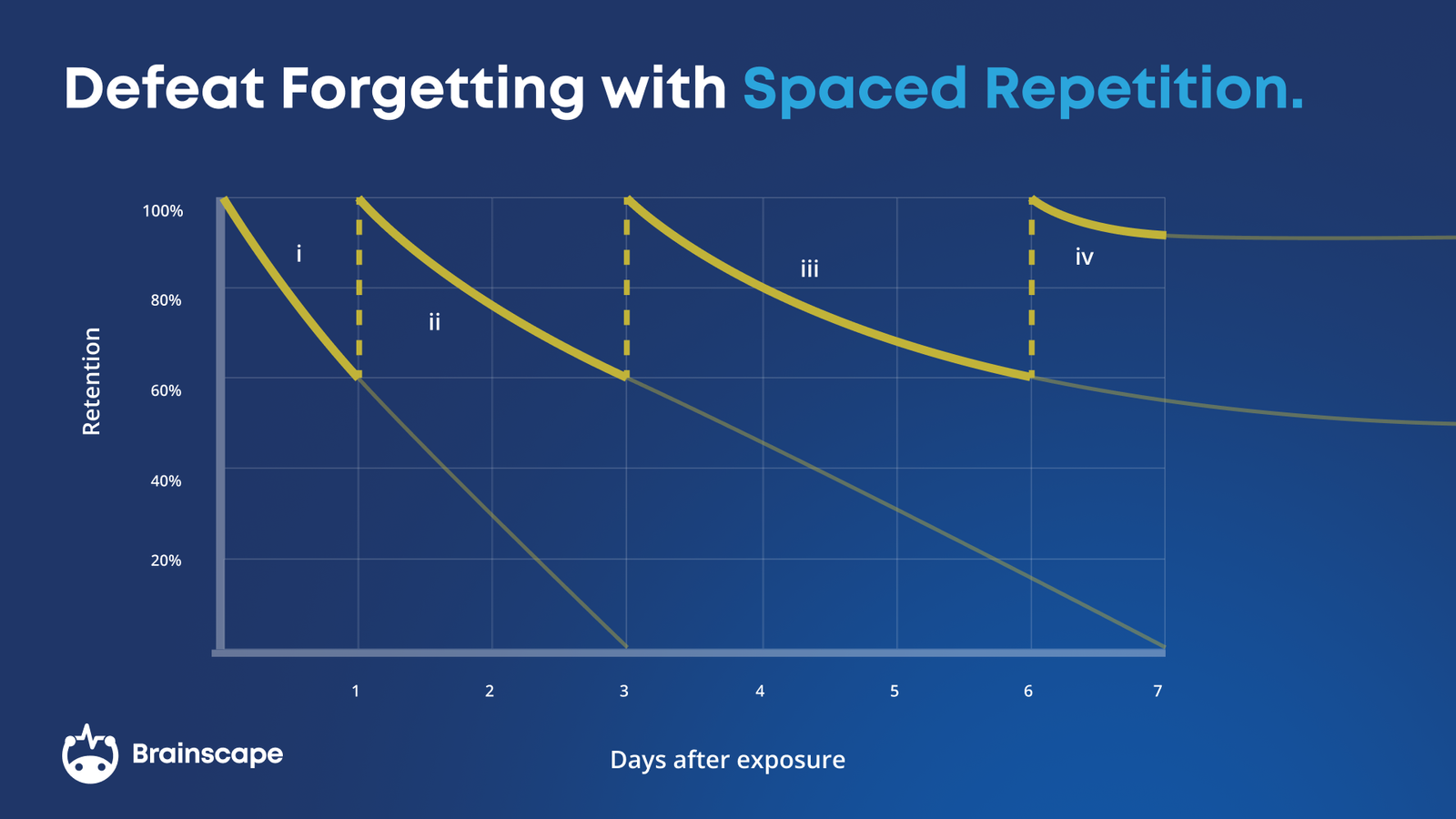

2. Retrieval strengthens memory and confidence ratings refine the timing

Every time you retrieve a piece of information, you reactivate its neural pathway, making it more durable. But not all retrievals are equally powerful. The most potent ones happen right at the edge of forgetting: a moment that’s difficult to time manually (Carpenter et al., 2022). This is where your confidence rating becomes a cognitive compass.

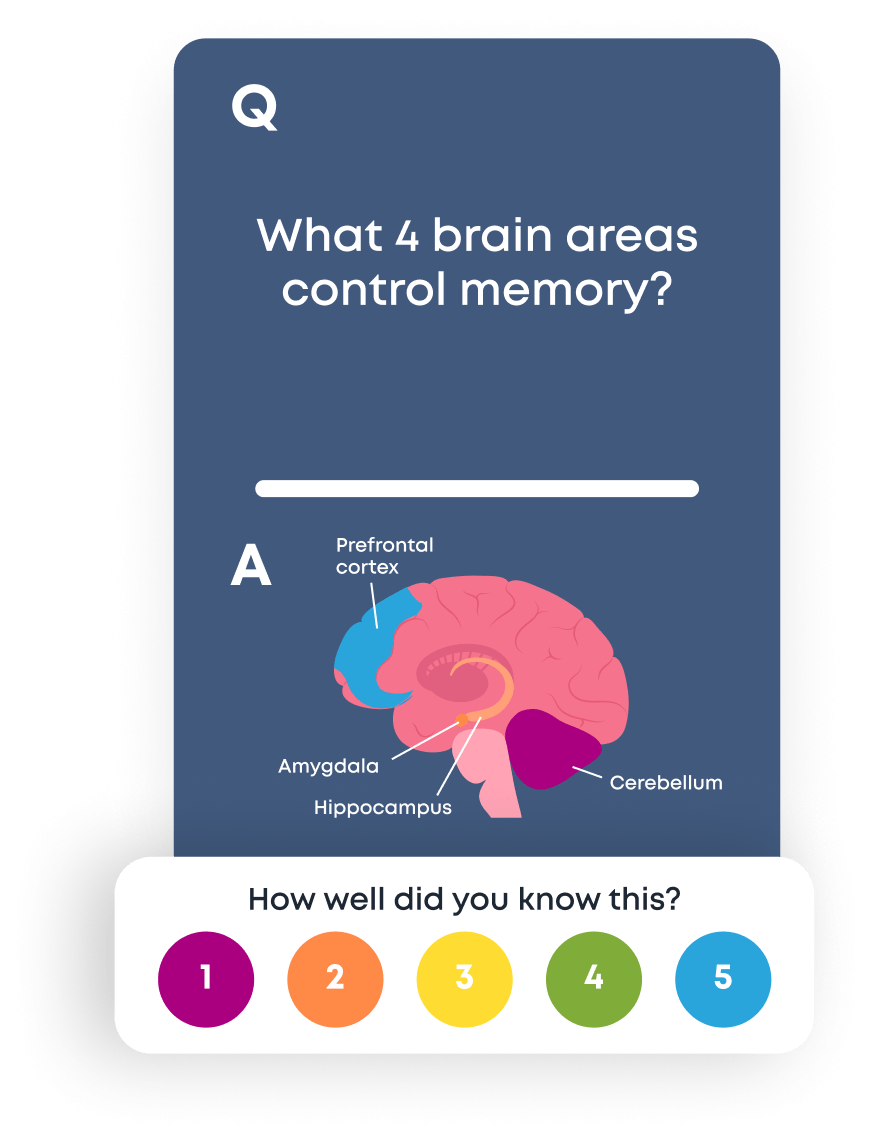

Adaptive flashcard systems do an excellent job of automating this process because they (1) break subjects down into their atomic facts, which you can then test yourself on and (2) they prompt you to rate how well you knew each one. In the case of Brainscape, you’re asked to rate your confidence on a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 being “not at all” and 5 being “totally confident”.

Low-confidence ratings tell the system you are drifting toward forgetting, so that flashcard should come back soon. High-confidence ratings tell the system the memory trace has stabilized, so it can safely be pushed further into the future. In this way, CBR dovetails the natural forgetting curve with metacognitive feedback to ensure you’re always practicing at the optimal difficulty point.

This is why consistent studying with CBR-powered flashcard apps is so incredibly efficient, allowing you to maximize your retention of new information.

3. CBR strengthens metacognition (your “inner coach”) through feedback loops

In everyday life, most people never receive feedback about whether their self-confidence matches their actual performance. CBR closes that loop.

Each time a flashcard returns, your brain checks: “Did the confidence rating I gave last time accurately predict how well I remembered it now?” When mismatches occur (e.g., you rated something a “5” but then completely forgot it), your metacognition adjusts. Over hundreds or thousands of repetitions, this calibration becomes increasingly precise (Flavell, 1979).

Essentially, CBR trains your metacognition: the internal coach in your head to make better calls, which pays dividends beyond flashcards, influencing essays, exams, presentations, and even real-world decision-making.

4. Personalized spacing reduces cognitive load while increasing learning density

Cognitive load theory tells us that your working memory can only juggle so much at once (Sweller et al., 2011). Traditional study methods often overwhelm this system by presenting too much information at the wrong time. CBR avoids this by filtering out well-known material and surfacing only the cards that sit near the edge of forgetting.

This reduces clutter and ensures that nearly every retrieval you perform is meaningful. The result is a study session that feels lighter cognitively but actually delivers more learning per minute because every flashcard is targeted to your current level of mastery!

5. The “sweet spot” of difficulty unlocks deeper encoding

Learning researchers often refer to a principle called desirable difficulty, the idea that the most efficient learning happens when the task is challenging but still achievable (Bjork & Bjork, 2011). CBR automatically keeps you in this zone. Because the timing of each flashcard is tied to your confidence, the material never becomes mindlessly easy or impossibly hard.

Instead, each retrieval pushes your brain just far enough to create strong, elaborated memory traces. This is why CBR study sessions often feel engaging and absorbing: they naturally hit the brain’s reward circuits by offering a steady stream of achievable micro-challenges.

So, to sum it all up, confidence-based repetition works because:

- You Spend More Time on Weaknesses: Traditional studying makes you re-read everything equally. CBR funnels your attention to the 20% of material that causes 80% of your errors (a nice little Pareto efficiency hack).

- You Don’t Get Overwhelmed: By naturally holding back material you know well, CBR avoids cognitive overload and burnout.

- It Builds Accurate Metacognition: You learn to predict your own memory, a hugely important skill for exams, professions, and lifelong mastery.

- It Keeps You in the Zone of Proximal Development: CBR pushes you just hard enough, but not harder than your brain can handle. It’s like having a tutor who always knows exactly when to challenge you and when to back off.

- It Dramatically Improves Long-Term Retention: Because spacing is calibrated to your memory curve, not a generic schedule.

Do you now see why CBR is considered such an efficient study method?

Now, let’s look at how you can apply it to your own learning, or to that of your students’ if you’re an educator…

How Can Learners Apply Confidence-Based Repetition?

By far, the easiest way to apply confidence-based repetition to any learning routine is with adaptive digital flashcards, so let’s start there. Then, we’ll look at some of the other methods you can use to improve your learning efficiency with CBR.

Use Digital Flashcard Apps with Confidence Ratings

There are a lot of flashcard apps out there, but the best ones offer confidence-based repetition and a five-bucket rating system (some only have two or three). Brainscape excels in all these areas so save yourself a Google and click on the link (#shamelessplug). Why do they work? Well, modern spaced-repetition systems:

- Compel you to retrieve information by answering questions

- Prompt you to rate your confidence, most helpfully on a scale of 1 to 5

- Use your rating to inform the spaced repetition system,

- Repeat cards back to you at the optimal time

If that ain’t confidence-based repetition, I’ll eat my hat!

(Thank goodness I’m not wearing a hat.)

Practice Self-Assessment Regularly

Even in non-flashcard settings, there are many ways you can reflect on what you’ve just learned and decide when next you should study it again:

- After reading a chapter or topic, ask yourself: “Could I explain this to someone right now?”

- Use 1–5 scales to judge your confidence

- Within 24 hours of initial exposure, perform the task of trying to explain that topic

- Now, compare your perceived mastery with your actual performance.

- Were the two aligned?

This works really well with longer, more complex topics. Flashcards are great at assessing your confidence in atomic concepts—single facts—whereas this kind of task could be used for whole textbook chapters or interwoven concepts. In other words, it’s the difference between:

Q: What organelle is responsible for producing ATP in eukaryotic cells?The answer is the mitochondrion, which is a discrete, single-response answer perfect for a flashcard.

And:

Q: Explain how the structure of the mitochondrion enables ATP production, and describe how this process connects to cellular respiration overall.

The answer is more complex. This question requires the learner to pull together multiple ideas: membrane structure, chemiosmosis, electron transport chain, Krebs cycle integration, and the overall role of mitochondrial design in energy production.

Truth be told, you CAN use flashcards for these types of questions (why not?) but you can also literally scan through the high-level topics in your study materials and attempt to explain each one from top to bottom, in as great detail as you can: a study technique called the Feynman Technique. (The kicker is that you need to explain it in simple terms a fifth grader can understand.)

Space Your Reviews Out Over Time

Break your study into short, daily sessions rather than marathon cramming sessions. Why? TL;DR, your brain has a finite memory for new information. Too much and it burns out. Too little and it gets bored. Read this article on cognitive load theory if you want to learn more.

Track Patterns in Overconfidence

If you consistently rate something as “easy” and forget it later, consider it a sign from the universe to modify your judgment strategy. This article on judgements of learning will show you how to do that.

How Can Educators Build CBR into Classroom Practice?

Confidence-Based Repetition can be a powerful teaching ally, but only if students actually know how to make accurate judgments of learning and receive frequent opportunities to practice them. The good news is that you don’t need specialized software to bring CBR principles into your classroom. You can build the habits manually, then let students transition to digital tools once the logic “clicks.”

1. Make Confidence Rating a Classroom Routine

After any retrieval activity (a quiz, a clicker question, a discussion prompt, a warm-up problem), ask students to rate their confidence in their answer.

Two simple formats work well, especially with younger learners:

- Thumb scale: thumbs up (confident), sideways (unsure), down (guess).

- Mini-scorecards: 1–5 on sticky notes or folded index cards.

This keeps the metacognitive loop alive: retrieval → feedback → confidence check.

Over time, students begin anticipating the confidence check, which quietly trains them to reflect more honestly on what they do and don’t know.

2. Use “Delayed Confidence Checks”

Right-after-the-lesson confidence is inflated because everything feels familiar. Instead, ask students to rate their confidence again later: at the end of class, at the start of the next period, or after a short unrelated activity. This shows students how dramatically confidence can change once the “illusion of fluency” wears off, and it teaches them why delayed judgments of learning (JOLs) are more predictive of durable learning.

3. Turn Quizzes Into Calibration Tools

You can transform quick quizzes into CBR engines by adding a single step:

- Students answer a set of retrieval questions.

- Before checking answers, they predict their score.

- Then they compare prediction vs. reality.

This tiny intervention has an outsized effect. Research shows that prediction–performance gaps sharpen metacognition far more effectively than traditional quizzing because students see their miscalibrations rather than vaguely feeling them.

4. Build CBR Into Group Work

In group discussions, ask each student to:

- Explain their reasoning for their answer

- Rate their confidence

- Compare with peers

Students quickly discover that confidence is not the same as correctness, a crucial realization for developing high-resolution JOLs. It also gives the more shy learners a safe structure for participating without needing to be “correct.”

5. Use Retrieval “Checkpoints” Throughout Long Lessons

For longer lectures or multi-step lessons, insert short checkpoints:

- “Answer this on your own.”

- “Rate your confidence from 1–5.”

- “Now turn and talk for 60 seconds.”

- “Re-rate your confidence.”

This creates a natural rhythm of retrieval, reflection, and recalibration. It also helps break the passive trance that makes students feel like they understand a topic while actually absorbing very little.

6. Pair CBR With Student-Created Questions

One of the best ways to deepen metacognition is to have students generate their own questions. After writing each question, have them:

- Assign a difficulty rating

- Predict how likely they are to remember the answer next week

- Revisit these predictions later

This blends generative processing with JOL training: two powerhouse learning techniques reinforcing each other.

7. Transition Students to Digital CBR Tools

Once students grasp the rhythm of retrieve → rate → repeat, they’ll benefit enormously from using adaptive digital flashcards that automate the scheduling, tracking, and optimizing of this cycle. The classroom routines I’ve just outlined in this section prepare them to use these systems effectively and prevent the “mindless clicking” that undermines spaced repetition.

So, What’s the Takeaway?

Your brain is constantly triaging information: Is this worth keeping? Or can I yeet it into the void?

Confidence ratings help the brain (and any software assisting it) make that call. It’s adaptive, efficient, and deeply personalized: a system that challenges you at precisely the right moment and backs off when your brain needs rest to consolidate.

Without it, studying becomes guesswork and inefficient.

With it, studying becomes strategic.

And while you can absolutely practice CBR on your own, modern adaptive flashcard platforms make it automatic. Apps like Brainscape are built around this exact mechanism, taking your confidence ratings and transforming them into individualized study sessions that drill you on your weaknesses, steadily turning them into strengths.

Your brain is a powerful computer. Learning the science behind it gives you the user manual!

*Insert evil, megalomaniacal laugh here*

Get Brainscape's Educator User Guide

Curious to learn more about how to introduce Brainscape into your physical or virtual classroom? Our Educator User Guide provides a detailed walkthrough of how to get set up. It'll also give you all the material you need to motivate for its adoption amongst your students, their parents, and/or the faculty of your school or college:

Additional Reading (if you’re a sucker for punishment)

If you loved this article, you’ll also love these other nerdy science articles we wrote about:

- The Cognitive Science of Studying: 16 Principles for Faster Learning

- What is Spaced Repetition (& Why Is It Key To All Learning)?

- What is Active Recall? How to Use It to Ace Your Exams

For even more articles on how to harness cognitive science to improve learning, focus, and memory, check out our ‘Science of Studying’ hub.

References

Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. In M. A. Gernsbacher, R. W. Pew, L. M. Hough, & J. R. Pomerantz (Eds.), Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society (pp. 56–64). Worth Publishers.

Carpenter, S. K., Cepeda, N. J., Rohrer, D., Kang, S. H. K., & Pashler, H. (2022). Using spacing to enhance diverse forms of learning: Review of recent research and implications for instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 34, 361–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09630-2

Ebbinghaus, H. (1885/1913). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology (H. A. Ruger & C. E. Bussenius, Trans.). Teachers College, Columbia University. (Original work published 1885)

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911.https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

Metcalfe, J. (2021). Metacognition: An agenda for cognitive science. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(1), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.10.006

Nelson, T. O., & Narens, L. (1990). Metamemory: A theoretical framework and new findings. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 26, 125–173.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-7421(08)60053-5

Prime, H., & Burns, E. (2020). The interplay of metacognition, memory, and learning strategies. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 38, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.01.001

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8126-4