Every few months, a familiar headline makes the rounds in education research circles: “Students learn more when they create their own flashcards.”

That conclusion makes sense. When students build cards, they have to paraphrase, organize, and ask themselves what matters. That is generative processing, which is a highly reliable method to deepen learning.

But is that all there is to it? Case closed?

Nope!

In real classrooms, there’s one variable that changes the whole conversation: time.

Once you take time seriously, the better question becomes: when is flashcard creation worth it, and when is it smarter to skip straight to studying?

In this article, we’ll discuss both and leave you with little doubt as to when students should rely on existing flashcards—perhaps those you’ve made for them—and when they should be tasked with creating their own!

Why Does Making Flashcards Improve Learning?

When students create flashcards, they do far more than just copy information. They make choices and engage in:

- Elaborative interrogation (“How would I explain this?”)

- Active recall (“What do I remember well enough to write?”)

- Generative processing (rephrasing and structuring ideas)

- Contextual encoding (rewriting the material in their own language)

Research consistently shows that generative activities improve comprehension and retention compared to passive review (Fiorella & Mayer, 2021). There’s also a motivational benefit: self-created materials often feel more personally relevant, which can increase engagement.

So yes, making flashcards can be powerful learning.

What Do Studies Often Miss About Flashcard Creation?

Time.

Making high-quality flashcards takes a lot of it. Students have to identify key concepts, decide what belongs on each card, write clear prompts, and then revise for accuracy and clarity. None of that effort is wasted, but it does come with an opportunity cost of time lost that could otherwise be spent on even more effective study activities (more on that later).

This is also where newer tools can change the equation.

Some digital flashcard apps now include AI assistance that helps students draft cards faster. For example, Brainscape offers bulk AI creation for generating many cards at once, plus Flashcard Copilot for building and refining cards one-by-one.

Used well, these features can reduce busywork and free up more time for retrieval practice. Used poorly, especially with bulk creation, it can take away the learning benefit students get from doing the thinking themselves.

Most studies still compare something like this:

- Group A: makes and studies flashcards

- Group B: studies premade flashcards

What they often do not control for is total time on task.

That leads to a practical question educators care about: what happens when students use the time saved by not creating flashcards to study even more effectively?

Can Studying Existing Flashcards Be Just as Effective?

Under the right conditions, yes.

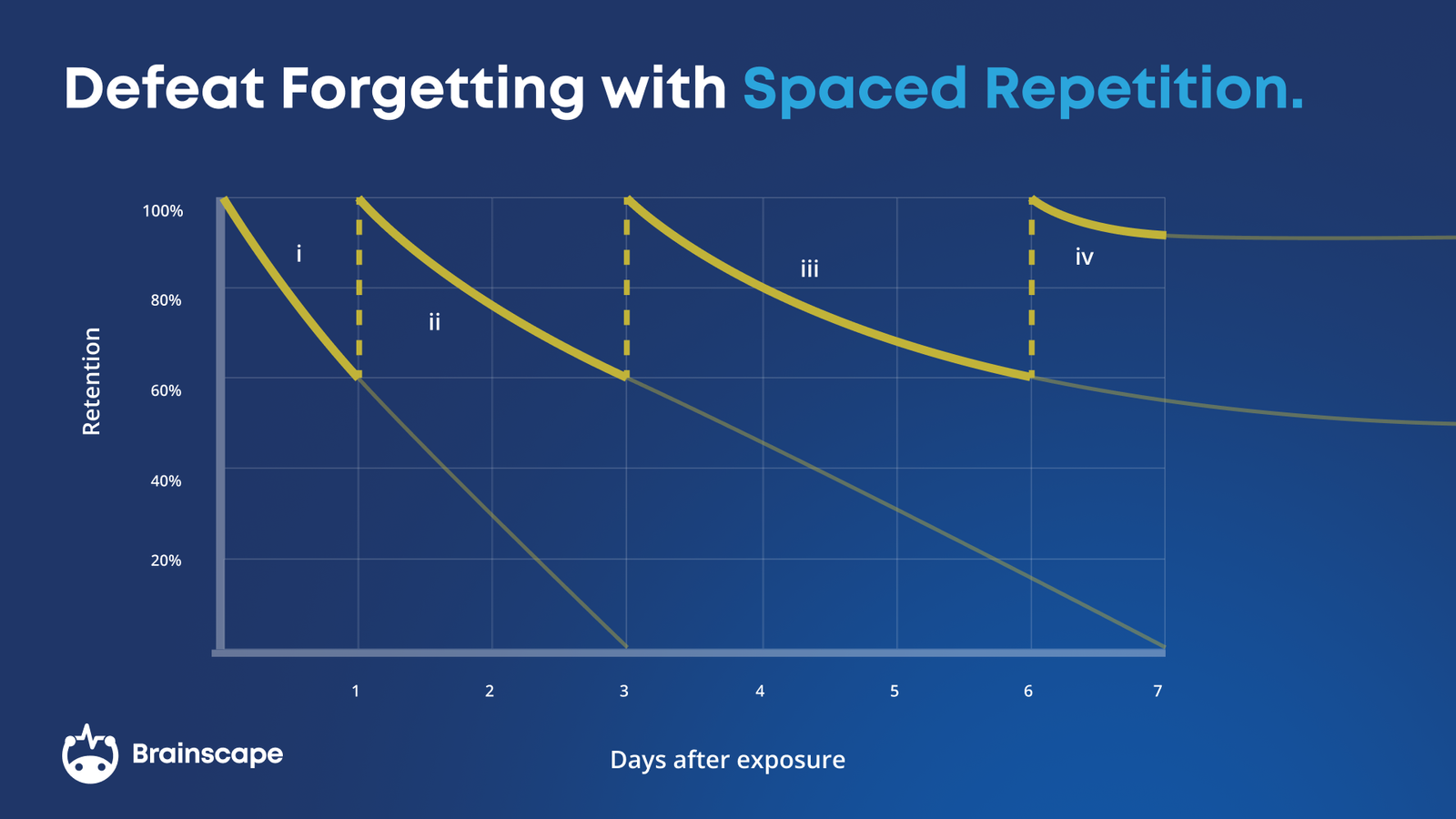

If students use high-quality flashcards and study them using spaced retrieval practice, the results can be excellent. Spaced retrieval, which means recalling information repeatedly over increasing intervals, has one of the largest effect sizes in learning science (Cepeda et al., 2009; Dunlosky et al., 2013).

When retrieval is frequent, effortful, and spread over days or weeks, long-term retention improves dramatically. This can feel slower because the overall study window is longer. But the net time cost is often lower: if students start with an existing set, they can spend fewer total minutes to reach mastery because they are not splitting time between making cards and studying them.

In many classrooms, students who skip flashcard creation can:

- Start retrieval practice sooner

- Keep it going longer

- Achieve similar or better retention in less total time

If a test is coming up soon, the tradeoff shifts even more. In that situation, the smarter move can be using an existing flashcard collection (or drafting a set with AI) and then putting most of the time into studying. What matters most is not how the cards were created. What matters is whether students practice retrieving and correcting mistakes.

When Should Students Make Their Own Flashcards?

Student-created flashcards are especially valuable when:

- The material is new or conceptually dense

- You want to foster understanding, not just recall

- They are building their metacognitive skills

- Students need practice organizing knowledge

- High-quality existing flashcards are not available, so someone has to create them

Flashcard creation works best as a learning activity, not just a study tool. It can be especially useful early in a unit, when slowing down to elaboratively process the material helps students build a solid mental framework.

If time is of the essence, but strong existing cards are still not available, that is when AI can help. Most digital flashcard apps can bulk-create flashcards with AI by uploading materials. But be careful. This can backfire by removing elaborative interrogation and by creating a false sense of progress. Students can feel like they have “learned” just because they generated the cards, then fail to replace that lost processing time with more spaced retrieval practice (link to our study).

That’s why Brainscape created Flashcard Copilot. It can help students tighten a question, trim a long answer, or add a clarifying example, without taking over the thinking. The student still has to decide what the card should test, and that decision is where much of the learning happens:

When Should Students Use Existing Flashcards?

Premade flashcards make the most sense when:

- Time is limited

- Accuracy and completeness are essential

- Students already have a baseline understanding

- Educators wish to make common resources for all students

- The content is image-heavy

A good flashcard collection made by you (their educator) or by an expert you trust (see Brainscape’s expert-created flashcards) removes friction and allows students to spend more time doing what actually strengthens memory: spaced retrieval.

(Read: How to Make Flashcards Students Actually Want to Study)

How Digital Flashcards Help Educators Balance Both Approaches

Digital flashcard apps such as Brainscape do not force educators to choose one approach. They support:

- Student-created flashcards, for generative learning

- Teacher-created or shared flashcards, aligned to curriculum and assessments

- Spaced, confidence-based repetition, so students spend more time on what they do not know yet

- AI-assisted authoring options, which can speed up creation when time is tight

That combination makes it easier for teachers to scaffold learning sequentially. Students can create cards early in a unit, then transition to a refined set later. Teachers can encourage consistent retrieval over time, rather than last-minute cramming.

Get Brainscape's Educator User Guide

Curious to learn more about how to introduce Brainscape’s digital flashcards into your physical or virtual classroom? Our Educator User Guide provides a detailed walkthrough of how to get set up. It'll also give you all the material you need to motivate for its adoption amongst your students, their parents, and/or the faculty of your school or college:

What Does the Research Still Need to Answer?

We need more studies that treat time as a real constraint, not an afterthought.

Specifically:

- Studies that equalize total study time across conditions

- Longitudinal designs that measure retention weeks or months later

- Classroom-based experiments with real students, real schedules, and real tradeoffs

Until then, the best approach is practical. Use flashcard creation when you want students to process and organize ideas. Use existing flashcards when you want students to practice retrieval consistently and build fluency.

If you have a classroom willing to explore these questions, Brainscape Labs encourages educators to design and test learning experiments in real instructional settings.

The Bottom Line for Educators

This debate is a good problem to have. It means students are using a study method that beats rereading, highlighting, and other passive review techniques.

It all boils down to choosing the right tool for the moment.

Have students slow down and generate flashcards when the goal is understanding and structure. Then help them speed up and retrieve when the goal is retention, fluency, and exam readiness.

Free Educator Resources For You:

- Brainscape Teacher’s Academy: Practical guides for implementing the cognitive science of learning and memory into your classroom, at scale.

- “Tips for Teachers” YouTube Channel: Short, research-backed advice and classroom strategies.

- The Cognitive Science of Studying: 16 Principles for Faster Learning (and how flashcards leverage each one)

References

Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2009). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 135(3), 354–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015166

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2021). Learning as a generative activity (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying. Science, 331(6018), 772–775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199327

Roediger, H. L., & Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2010.09.003