If you’ve ever rolled out a shiny new flashcard system, only to watch student engagement flatline, you’re not alone.

Educators often assume that motivation lives in the platform: gamification, streaks, reminders, and grades. Those things can help, and so can making flashcard study part of a course grade.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: no amount of tech can rescue bad flashcards.

Most of what follows applies whether your students are using paper flashcards or a digital flashcard app, although a few tips toward the end are easier to implement on digital platforms.

If flashcards aren’t relevant, readable, or cognitively manageable, students won’t study them, no matter how elegant the app. Motivation does not just come from rewards. It comes from perceived usefulness and effort-to-value ratio.

Let’s talk about how to build flashcards that students actually want to study.

Why Do Students Avoid Studying Flashcards?

From a cognitive science perspective, motivation often collapses when cognitive load exceeds perceived payoff.

Students disengage when flashcards:

- Feel disconnected from assessments

- Are dense, cluttered, or exhausting to read

- Demand too much free recall, too often

- Blur together instead of sharpening distinctions

In short, students stop studying when flashcards feel like work without a clear return.

The solution is better flashcard design, and we’ll talk about that in just a bit, but first…

Should Flashcards Be Tied to Tests?

Yes. Unequivocally. (Well, for the most part.)

Few phrases kill motivation faster than: “This won’t be on the test.”

From the learner’s perspective, relevance is motivational oxygen. Flashcards signal value when they map directly, or transparently, to assessments, which in turn increases effort and persistence (Expectancy-Value Theory; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). And despite all the hand-wringing about “teaching to the test,” there’s nothing inherently wrong with aligning study materials to assessed standards (Perera et al., 2016). The real problem is narrow item-drilling when the test itself is too limited, not making expectations clear, and preparing students for what they will be evaluated on.

This does not mean every flashcard must be a test question. But students should be able to see a clear throughline:

- Key terms they’ll be tested on

- Concepts that underpin exam questions

- Skills that transfer to graded performance

Flashcards should feel like test preparation, not an optional sidequest.

What Makes a Flashcard Readable?

Readability is not a cosmetic concern. It is a cognitive load issue.

According to Cognitive Load Theory, learning materials should minimize unnecessary processing so students can focus on the core idea (Sweller et al., 2019).

Well-designed flashcards tend to share these traits:

- Short, focused answers (one idea per card)

- Clear formatting for lists or steps

- Clearly identified key terms via bold text or other formatting options

- Visual separation between main ideas and supporting details

Poorly designed flashcards ask students to decode structure before they can retrieve content, and that friction erodes motivation.

Why Are “Fields” So Effective in Flashcards?

One of the most powerful and underused design principles is separating core knowledge from elaboration.

In digital flashcard apps like Brainscape, Remnote, and Anki, this often looks like:

- Main Answer field: crisp, essential response

- Footnote field: examples, explanations, nuances, exceptions

- Clarifier field: a quick hint that separates similar ideas (for example, a definition boundary, a common mix-up, or “don’t confuse this with…”), without giving away the full answer

This design aligns well with generative processing and cognitive load management. First, students retrieve the core idea. Then, they can optionally deepen their understanding with elaboration.

It also prevents flashcards from turning into mini-textbooks, which is a guaranteed motivation killer.

Read: The Complete Guide To Making & Studying Flashcards

Are Free Recall Flashcards Good or Bad?

Free recall cards, such as “Describe how process X works” (which then prompts learners to provide a much longer, more in-depth answer) are powerful for tying multiple concepts together in a more complex mental web. But like espresso, they’re best used in small doses.

Free recall is when students try to pull a comprehensive answer from memory with no options or cues, rather than recognizing it from a list.

Research shows that free recall strengthens retrieval pathways and transfer (Karpicke & Blunt, 2011). However, too many open-ended prompts increase mental fatigue, slow study pace, and discourage repeated practice.

Here are three principles to keep in mind:

- Use free recall flashcards occasionally, for synthesis

- Use crisp prompts with bounded answers most of the time

- Push complexity into footnotes rather than the main answer

Flashcards should feel challenging but doable, not like essay exams in disguise.

Should Teachers or Students Create the Flashcards?

Both approaches work, but they serve different purposes.

First, a quick practical note: with digital flashcard platforms, teachers can create (or import) one set of flashcards and share it with an entire class before the lesson. Much quicker than making 30 separate decks by hand!

When educators create flashcards, quality control is highest. This is ideal when you need your flashcards to align closely with your assessments or introduce complex material as part of the initial delivery. It’s also useful for teachers to model what good flashcards look like before students make their own.

When students create flashcards, their engagement with the material results in deeper learning. Flashcard creation activates a number of useful processes in students:

- Elaborative interrogation (“How would I explain this?”)

- Metacognition (“Do I really understand this?”)

- Generative processing through rephrasing and organization

The act of making flashcards is incredibly valuable for learning.

(Read: Should Students Use Existing Flashcards or Make Their Own?)

Should Students Be Graded on Flashcard Creation?

Yes, at first, if you want them to take it seriously. If students are responsible for creating flashcards, for themselves or peers, grading them on quality can help establish the habit and set expectations. Once students consistently demonstrate good flashcard-making skills, you can often ease off the grading and keep it as an occasional check-in.

An effective rubric might include:

- Accuracy

- Clarity

- Following the rule of one concept per card

- Effective use of main answer vs. footnote

- Differentiation between similar concepts

Sure, reviewing flashcards takes time. But the payoff is threefold: students learn the material better, they learn how to learn, and their resulting flashcards are actually worth studying!

Logistically, “grading” looks different depending on the format. With paper flashcards, students can submit a small sample physically (or photograph a sample for easier review). With digital flashcards, having students share a link to their flashcard set makes review and feedback much more manageable.

How Flashcard Apps like Brainscape Help Students Want to Study Flashcards

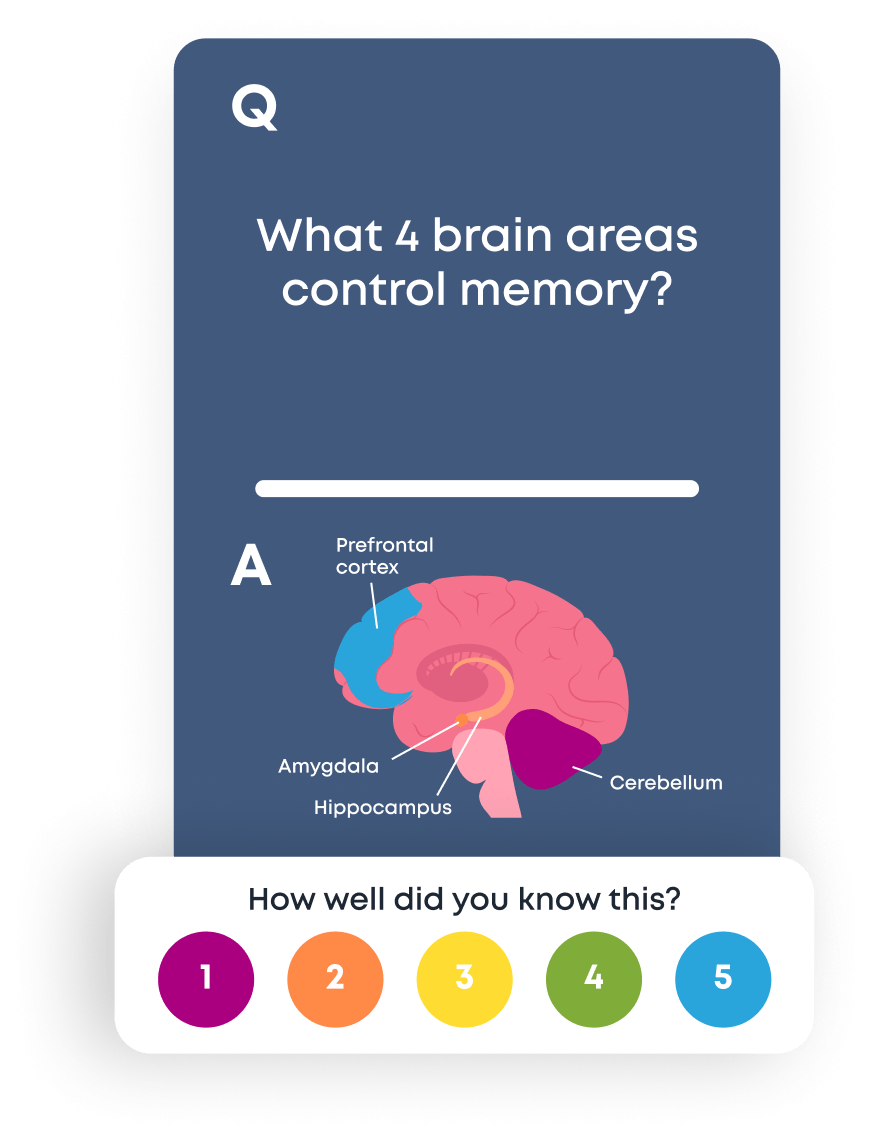

Digital flashcard apps such as Anki and Brainscape help students learn by combining active recall with a spaced repetition system called Confidence-Based Repetition. After each card, students rate how well they knew the answer. The app uses that self-rating to decide what shows up next, so they spend more time on what they’re shaky on and less time re-reading what they already know.

That “just right” pacing matters because motivation collapses at the two extremes. Students get bored when they keep seeing easy cards, and they get overwhelmed when hard cards pile up too fast. Confidence-based repetition keeps the challenge level matched to the individual student’s strengths and gaps, so studying feels achievable at all times.

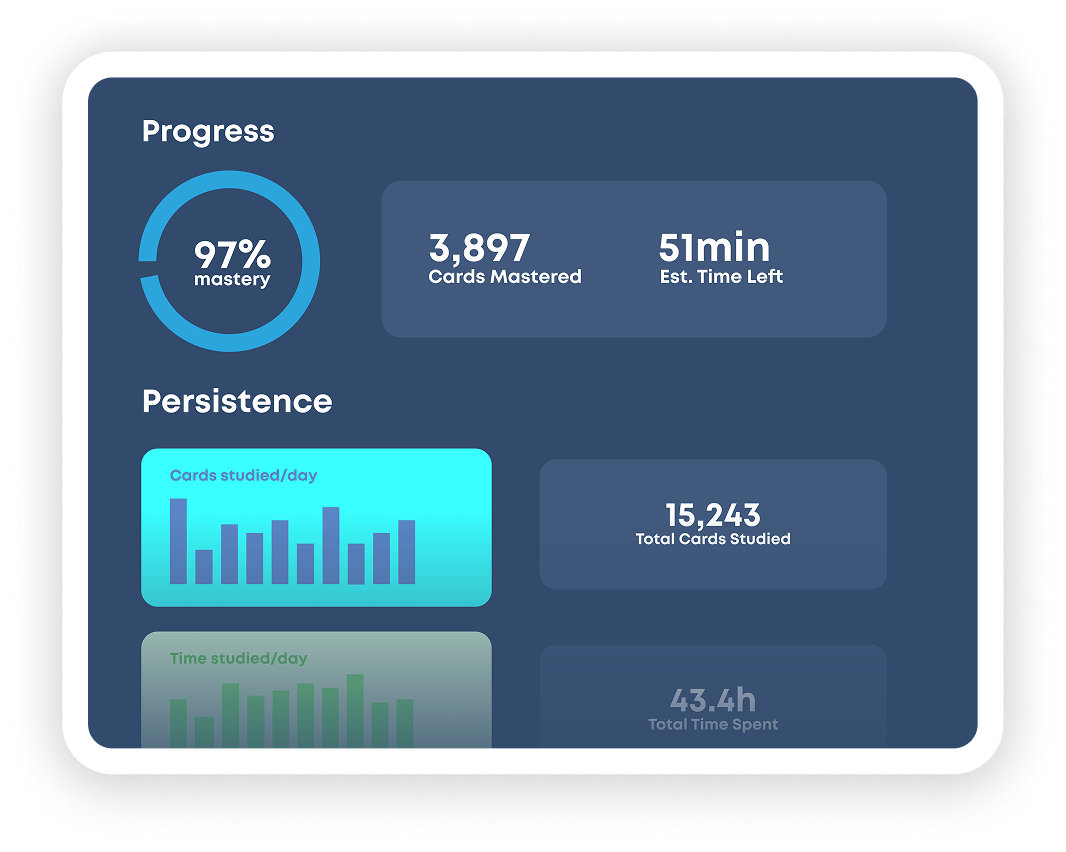

It also helps that the experience is designed to show progress quickly. Instead of staring at a giant, vague pile of content, students study in short rounds with frequent checkpoints. They can see mastery increase as they go. Many apps, such as Quizlet and Brainscape, also include features like streaks and study metrics that make improvement visible, which can be more motivating than reminders or grade pressure.

When the flashcards themselves are clear, relevant, and aligned with how memory works, features like these can amplify what’s already working. The result is a study experience that feels structured, avoids overwhelm, and rewards consistency.

Get Brainscape's Educator User Guide

Curious to learn more about how to introduce Brainscape into your physical or virtual classroom? Our Educator User Guide provides a detailed walkthrough of how to get set up. It'll also give you all the material you need to motivate adoption among your students, their parents, or the faculty of your school or college:

The Bottom Line for Educators

Students don’t avoid flashcards because they’re lazy. They avoid flashcards that feel irrelevant, exhausting, or inefficient.

If you want buy-in, the fastest path is to make the value obvious. Tie at least some cards directly to what students will be assessed on, keep each card focused on one idea, and write prompts that feel challenging but doable.

When the workload matches the payoff, students are far more likely to come back tomorrow and the next day. Build better flashcards, and motivation follows.

Free Educator Resources For You:

- Brainscape Teacher’s Academy: Practical guides for implementing the cognitive science of learning and memory into your classroom, at scale.

- “Tips for Teachers” YouTube Channel: Short, research-backed advice and classroom strategies.

- The Cognitive Science of Studying: 16 Principles for Faster Learning (and how flashcards leverage each one)

References

Dunlosky, J., & Rawson, K. A. (2020). Practice tests, spaced practice, and successive relearning. Educational Psychology Review, 32, 207–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09510-6

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2021). Learning as a generative activity (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying. Science, 331(6018), 772–775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199327

Perera, R. M., Meyer, K., & Emily Markovich Morris, R. H. (2016, July 29). Teaching to the test: Hype or reality?. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/teaching-to-the-test-hype-or-reality/

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2019). Cognitive load theory (2nd ed.). Springer.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81.